Unless you’re a Classic Rock music nerd/liner note reader, the name Jesse Ed Davis is probably unfamiliar to your eyes. But you’ve definitely heard his guitar stylings.

That’s him ripping the searing electric solo on Jackson Browne’s “Doctor My Eyes.” That’s him strumming the lush, syncopated guitar intro on Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night.” He plays lead on Bob Dylan’s “When I Paint My Masterpiece” and “Watching the River Flow.” And that’s him in the background at the Concert for Bangla Desh: George Harrison had him as a safeguard in case a drug-addled Eric Clapton didn’t show up.

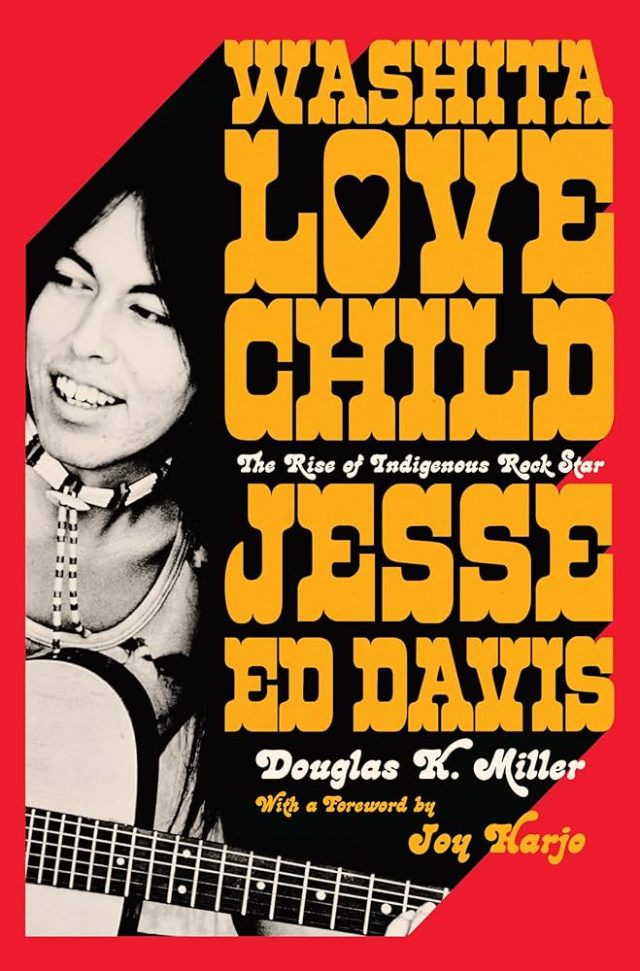

Now, Douglas K. Miller – a professor of history at Oklahoma State University, former musician, and author of other works on Native American History – tells the guitarist’s story in Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis (464 pp., $32.50, Liveright).

Throughout his career a sideman, Davis shared the concert stage and/or recording studio with Bob Dylan, Leon Russell, the Rolling Stones, all the Beatles sans Paul, Taj Mahal, Eric Clapton, Gene Clark, and Rod Stewart. Gregg Allman has gone on record saying that Davis’ slide guitar playing on a Taj Mahal record directly influenced his brother Duane to take up the style and become one if its greatest practitioners.

Davis always preferred to be known as a guitarist who happened to be Native American instead of a Native American guitarist. His ethnic background from multiple Indian tribes (mainly Comanche and Kiowa) gave him a striking visual look unlike any other Classic Rocker, but also opened him up to racism in and out of the music industry.

Davis turned frontman for three solo albums in the early ‘70s: ¡Jesse Davis! (which includes the autobiographical track that gives this bio its name), Ululu, and Keep Me Comin’. And while he had his limitations as a vocalist, each showcases his distinctive playing style, with a sound akin to The Band/Little Feat/Leon Russell/Dr. John.

And while he took great pride in his playing, he could also be dismissive of it. That “Doctor My Eyes” solo? Davis played it exactly once, with no rehearsal, and that’s what you hear on the record. It’s his most famous playing, yet for years he would badmouth it to anyone who’d listen.

He could also self-sabotage. Davis and most of his admirers considered Keep Me Comin’ the record that would finally break him as a solo artist. But after rejecting a cover featuring art that (again) would lean on hid Indigenous identity, he replaced it with a stern picture of himself, arms folded, against a backdrop of nudie magazine cut outs, barely airbrushed. Many outlets refused to carry it.

His music and his personal behavior would continue to get more erratic as his drug use – usually heroin – increased.

Still, his skills were in demand. He was in John Lennon’s band during the “Lost Weekend” and recordings of Rock and Roll and Walls and Bridges. He nearly stepped in as a Rolling Stone for a 1973 tour when Keith Richards’ legal issues almost prevented him from playing. He joined Rod Stewart and the Faces for a tour just as Stewart’s own star was rising.

In the last years of his life, Davis struggled. With addiction, with romantic relationships, multiple stints in rehab, and more blown opportunities. It wasn’t uncommon for friends to not hear from him for months, then get a call from the guitarist asking for money.

And while a stint in the band Grafitti Man [sic] fronted by the Indigenous poet John Trudell helped connect him with his heritage via their collaborative and esoteric music (Dylan was a great fan), it wasn’t enough to keep the proverbial bad spirits at bay.

Miller conducted scores of original interviews for the book, while using a treasure trove of archival materials, some provided by Davis’ own family. Throughout, his admiration and love for Davis and his music are evident, though his writing is honest about the darker episodes and behavior of his subject.

Jesse Ed Davis died in 1988 at the age of 43 when police found him slumped on the floor of an apartment complex laundry room, his body showing fresh evidence of heroin use. An ignoble end for the Oklahoma native whose admirers included so many titans of Classic Rock.

This review originally appeared at HoustonPress.com