Skip Spence was a near-founding member of the Jefferson Airplane, a founding member of the well-regarded Moby Grape, and released a solo album that is cherished by rock critics and famous fans.

Unfortunately, his name usually comes up in conversation not about San Francisco’s trailblazing musicians, but as a drug casualty who fried out his brain, and someone who struggled with mental illness. Just like Pink Floyd’s Syd Barrett, Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green, and the 13th Floor Elevators’ Roky Erickson. Guys who took their pharmaceutical adventures a little too far and never quite returned whole.

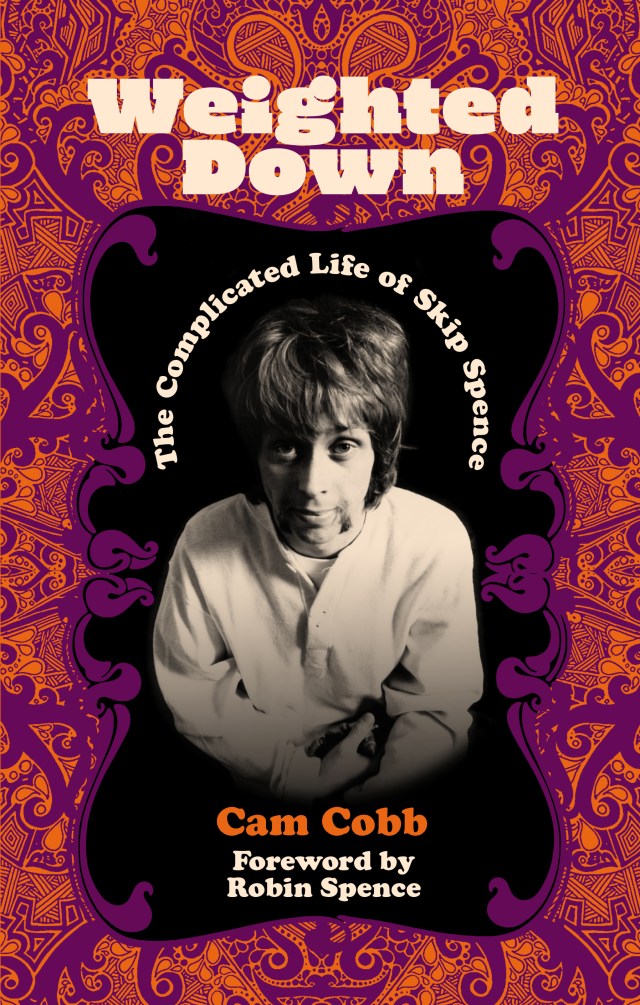

But fortunately, author Cam Cobb navigates down the rabbit hole of the life and music of the free-spirited but troubled soul in Weighted Down: The Complicated Life of Skip Spence (384 pp., $36.99, Omnibus Press).

Though he started in folk music, Skip Spence soon gravitated toward the rock and roll that was becoming more and more prevalent in the rehearsal spaces, clubs, and theaters of San Francisco in 1965/66. He was asked to join the Jefferson Airplane shortly after they formed—but as drummer rather than the singer/guitarist he had been to that point.

After playing that role in shows an on their debut album The Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, he was let go for (pick your reason) conflicts with singer Marty Balin, a tendency to disappear at times, or his stated desire to move back to a more prominent musical role.

He got that as one of three guitarists in Moby Grape, and band whose name should be uttered today in the same general breath as the Airplane, Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, and Santana as heavy hitters from the City by the Bay. The material was great, they could play rock, blues, jazz, country, and psychedelia, and all five members sang lead at some point. The buzz on them was huge.

But, as Cobb details both in this book and his previous Moby Grape boy, What’s Big and Purple and Lives in the Ocean?, a series of unfortunate events—several out of their control—torpedoed the band’s chance at national success.

Weighted Down benefits from Cobb’s extensive interviews with several Moby Grape members and Spence’s family, though Spence’s own voice does not crop up often. Cobb’s prose sometimes also reads as methodical and fact-based as one of the tour itineraries printed in the back.

All the while the band was forced to compete with an entirely fake “Moby Grape” also touring the country. Former manager Matthew Katz claimed he owned the name and could create any lineup he pleased. All parties would spend decades in and out of courtrooms.

Spence initially parted ways with Moby Grape after their second album when, under the influence of lots of drugs and a girlfriend who claimed to be a witch, he tried to attack two bandmates with an axe. He was then committed to Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital. Skip Spence was 22 years old, married, with three children and another on the way.

In 1969, Spence would release his only solo record—Oar—on which he wrote and sang all of the songs and played every instrument. It bombed commercially. But in years after became a cult hit favorite, reissued in various formats with more and more bonus material. It was a raw, and sometimes spooky, look into the state of mind of Spence at the time, in which he sometimes heard voices.

Over the next decades, Spence would alternate between drug addiction and sobriety; between homes, churches mental wards, halfway houses and jails; in and out of various Moby Grape reunions and new musical collaborations, and record projects that never went anywhere, even as his legend grew.

Skip Spence died in 1999 at the age of 52 from lung cancer, but his health had been in decline for years. Only a few weeks after, the tribute album that was already in the can, More Oar, was released. Famous fans like Robert Plant (who especially loved Moby Grape), Beck, Tom Waits, and Mudhoney participated. And in 2018, a 3-disc Oar box set appeared to hosannahs.

In his intro to Weighted Down, Cobb says he hoped that his work clarifies or at least finds common ground between the “myth and truth” of Skip Spence. That it does—and in abundance.

This article originally appeared at HoustonPress.com